I spent this glorious weekend on the wrong side of a library (that is, the inside). But despite my disappointment at missing the beautiful April weather, I did get a lot of interesting research done. I'm currently working on a paper about U.S. radio broadcasting in Iraq and Afghanistan, and in the course of my research I stumbled across an article describing Duke Ellington's tour of the Middle East in 1963.

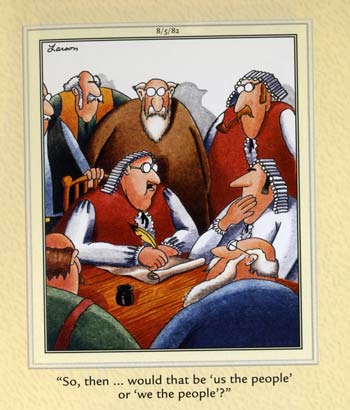

I spent this glorious weekend on the wrong side of a library (that is, the inside). But despite my disappointment at missing the beautiful April weather, I did get a lot of interesting research done. I'm currently working on a paper about U.S. radio broadcasting in Iraq and Afghanistan, and in the course of my research I stumbled across an article describing Duke Ellington's tour of the Middle East in 1963.Although their shows were well attended, Ellington and his orchestra were disappointed to find that they were consistently playing for the nations' elites, and not for "the people," leading their sympathetic State Department handler to conclude that they had misunderstood the meaning of the word "people."

For the jazz musicians, the "people" were the working class men (and women) on the street. For the State Department, the "people" were the elites who were best positioned to help the U.S. government realize its foreign policy objectives abroad. Underneath these assumptions are questions about legitimacy. What makes a legitimate audience for public diplomacy? For the United States, the answer is often related to national security concerns. U.S. public diplomacy has traditionally been best funded during times when the nation perceived itself to be threatened (by Nazis, Soviets or terrorists, for example) and public diplomacy was seen as a tactic to counter opposition.

But by categorizing the people of foreign nations according to their legitimacy, or their utility, does public diplomacy not risk isolating vast segments of the population? And what does that reveal about underlying assumptions about those people and their culture? Somehow targeting specific segments of a society for message reception seems a little cynical and self-serving. At the very least, it seems less likely to succeed than working together with foreign publics to construct a message people in both countries can support.

No comments:

Post a Comment